This category includes acts performed without intent or malicious purpose or in ignorance by an authorized user. When people use information assets, mistakes happen. Similar errors happen when people fail to follow established policy. Inexperience, improper training, and incorrect assumptions are just a few things that can cause human error or failure. Regardless of the cause, even innocuous mistakes can produce extensive damage. In 2017, an employee debugging an issue with the Amazon Web Services (AWS) billing system took more servers down than he was supposed to, resulting in a chain reaction that took down several large Internet sites. It took time to restart the downed systems, resulting in extended outages for several online vendors, while other sites were unable to fully operate due to unavailable AWS services.

In 1997, a simple keyboarding error caused worldwide Internet outages

In April 1997, the core of the Internet suffered a disaster. Internet service providers lost connectivity with other ISPs due to an error in a routine Internet router-table update process. The resulting outage effectively shut down a major portion of the Internet for at least twenty minutes. It has been estimated that about 45 percent of Internet users were affected. In July 1997, the Internet went through yet another more critical global shutdown for millions of users. An accidental upload of a corrupt database to the Internet’s root domain servers occurred. Because this provides the ability to address hosts on the Net by name (i.e., eds.com), it was impossible to send e-mail or access Web sites within the dot com and dot net domains for several hours. The dot com domain comprises a majority of the commercial enterprise users of the Internet.

One of the greatest threats to an organization’s information security is its own employees, as they are the threat agents closest to the information. Because employees use data and information in everyday activities to conduct the organization’s business, their mistakes represent a serious threat to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data—even, as Figure 2 dash 8 suggests, relative to threats from outsiders. Employee mistakes can easily lead to revelation of classified data, entry of erroneous data, accidental deletion or modification of data, storage of data in unprotected areas, and failure to protect information. Leaving classified information in unprotected areas, such as on a desktop, on a Web site, or even in the trash can, is as much a threat as a person who seeks to exploit the information, because the carelessness can create a vulnerability and thus an opportunity for an attacker. However, if someone damages or destroys data on purpose, the act belongs to a different threat category.

In 2014, New York’s Metro-North railroad lost power when one of its two power supply units was taken offline for repairs. Repair technicians apparently failed to note the interconnection between the systems, resulting in a two-hour power loss. Similarly, in 2016, Telstra customers in several major cities across Australia lost communications for more than two hours due to an undisclosed human error.

Human error or failure often can be prevented with training, ongoing awareness activities, and controls. These controls range from simple activities, such as requiring the user to type a critical command twice, to more complex procedures, such as verifying commands by a second party. An example of the latter is the performance of key recovery actions in PKI systems. Many military applications have robust, dual-approval controls built in. Some systems that have a high potential for data loss or system outages use expert systems to monitor human actions and request confirmation of critical inputs.

Social Engineering

In the context of information security, social engineering is used by attackers to gain system access or information that may lead to system access. There are several social engineering techniques, which usually involve a perpetrator posing as a person who is higher in the organizational hierarchy than the victim. To prepare for this false representation, the perpetrator already may have used social engineering tactics against others in the organization to collect seemingly unrelated information that, when used together, makes the false representation more credible. For instance, anyone can check a company’s Web site or even call the main switchboard to get the name of the CIO; an attacker may then obtain even more information by calling others in the company and falsely asserting his or her authority by mentioning the CIO’s name. Social engineering attacks may involve people posing as new employees or as current employees requesting assistance to prevent getting fired. Sometimes attackers threaten, cajole, or beg to sway the target.

Business E-Mail Compromise (BEC)

A new type of social engineering attack has surfaced in the last few years. Business e-mail compromise (BEC) combines the exploit of social engineering with the compromise of an organization’s e-mail system. An attacker gains access to the system either through another social engineering attack or technical exploit, and then proceeds to request that employees within the organization, usually administrative assistants to high-level executives, transfer funds to an outside account or purchase gift cards and send them to someone outside the organization. According to the FBI, almost 24,000 BEC complaints were filed in 2019, with projected losses of more than $1.7 billion. Reporting these crimes quickly is the key to a successful resolution. The FBI Internet Crime Complaint Center’s Recovery Asset Team has made great strides in freezing and recovering finances that are stolen through these types of scams, as long as they are reported quickly and the perpetrators are inside the United States.

Advance-Fee Fraud

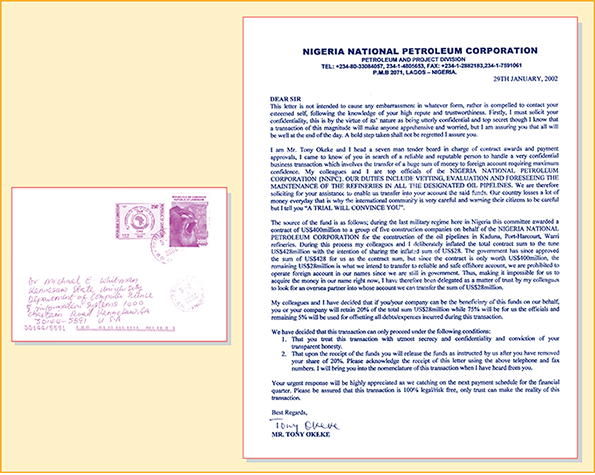

Another social engineering attack called the advance-fee fraud (AFF), internationally known as the 4-1-9 fraud, is named after a section of the Nigerian penal code. The perpetrators of 4-1-9 schemes often use the names of fictitious companies, such as the Nigerian National Petroleum Company. Alternatively, they may invent other entities, such as a bank, government agency, long-lost relative, lottery, or other nongovernmental organization. See Figure 2-9 for a sample letter used for this type of scheme.

The scam is notorious for stealing funds from credulous people, first by requiring them to participate in a proposed money-making venture by sending money up front, and then by soliciting an endless series of fees. These 4-1-9 schemes are even suspected to involve kidnapping, extortion, and murder. According to The 4-1-9 Coalition, more than $100 billion has been swindled from victims as of 2020.

Phishing

Many other attacks involve social engineering. One such attack is described by the Computer Emergency Response Team and Coordination Center (CERT and CC):

CERT and CC has received several incident reports concerning users receiving requests to take an action that results in the capturing of their password. The request could come in the form of an e-mail message, a broadcast, or a telephone call. The latest ploy instructs the user to run a “test” program, previously installed by the intruder, which will prompt the user for his or her password. When the user executes the program, the user’s name and password are e-mailed to a remote site. These messages can appear to be from a site administrator or root. In reality, they may have been sent by an individual at a remote site, who is trying to gain access or additional access to the local machine via the user’s account.

While this attack may seem crude to experienced users, the fact is that many e-mail users have fallen for it. These tricks and similar variants are called phishing attacks. They gained national recognition with the AOL phishing attacks that were widely reported in the late 1990s, in which attackers posing as AOL technicians attempted to get login credentials from AOL subscribers. The practice became so widespread that AOL added a warning to all official correspondence that no AOL employee would ever ask for password or billing information. Variants of phishing attacks can leverage their purely social engineering aspects with a technical angle, such as that used in pharming, spoofing, and redirection attacks, as discussed later in this module.

Another variant is spear phishing. While normal phishing attacks target as many recipients as possible, a spear phisher sends a message to a small group or even one person. The message appears to be from an employer, a colleague, or other legitimate correspondent. This attack sometimes targets users of a certain product or Web site. When this attack is directed at a specific person, it is called spear phishing. When the intended victim is a senior executive, it may be called whaling or whale phishing.

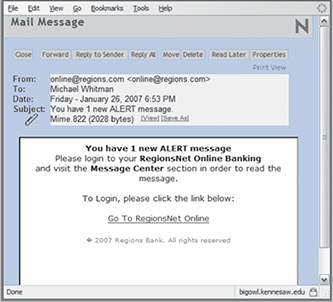

Phishing attacks use two primary techniques, often in combination with one another: URL manipulation and Web site forgery. In Uniform Resource Locator (URL) manipulation, attackers send an HTML-embedded e-mail message or a hyperlink whose HTML code opens a forged Web site. For example, Figure 2-10 shows an e-mail that appears to have come from Regions Bank. Phishers typically use the names of large banks or retailers because potential targets are more likely to have accounts with them. In Figure 2-11, the link appears to be to Regions Net Online, but the HTML code actually links the user to a Web site in Poland. This is a very simple example; many phishing attackers use sophisticated simulated Web sites in their e-mails, usually copied from actual Web sites. Companies that are commonly used in phishing attacks include banks, lottery organizations, and software companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Google.

In the forged Web site shown in Figure 2-11, the page looks legitimate; when users click either of the bottom two buttons—Personal Banking Demo or Enroll in RegionsNet—they are directed to the authentic bank Web page. The Access Accounts button, however, links to another simulated page that looks just like the real bank login Web page. When victims type their banking ID and password, the attacker records that information and displays a message that the Web site is now offline. The attackers can use the recorded credentials to perform transactions, including fund transfers, bill payments, or loan requests.

People can use their Web browsers to report suspicious Web sites that might have been used in phishing attacks. Figure 2-12 shows the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Web site that provides instructions on reporting IRS-spoofed phishing attacks.

Pretexting

Pretexting, sometimes referred to as phone phishing or voice phishing (vishing), is pure social engineering. The attacker calls a potential victim on the telephone and pretends to be an authority figure to gain access to private or confidential information, such as health, employment, or financial records. The attacker may impersonate someone who is known to the potential victim only by reputation. If your telephone rings and the caller ID feature shows the name of your bank, you might be more likely to reveal your account number. Likewise, if your phone displays the name of your doctor, you may be more inclined to reveal personal information than you might otherwise. Be careful; VOIP phone services have made it easy to spoof caller ID, and you can never be sure who you are talking to. Pretexting is generally considered pretending to be a person you are not, whereas phishing is pretending to represent an organization via a Web site or HTML e-mail. This can be a blurry distinction.

0 comments:

Post a Comment