This category of threat involves the deliberate sabotage of a computer system or business or acts of vandalism to destroy an asset or damage the image of an organization. These acts can range from petty vandalism by employees to organized sabotage against an organization.

Although they might not be financially devastating, attacks on the image of an organization are serious. Vandalism to a Web site can erode consumer confidence, diminishing an organization’s sales, net worth, and reputation. For example, in the early hours of July 13, 2001, a group known as Fluffi Bunni left its mark on the home page of the SysAdmin, Audit, Network, and Security (SANS) Institute, a cooperative research and education organization. This event was particularly embarrassing to SANS Institute management because the organization provides security instruction and certification. The defacement read, “Would you really trust these guys to teach you security?” At least one member of the group was subsequently arrested by British authorities.

Online Activism

There are innumerable reports of hackers accessing systems and damaging or destroying critical data. Hacked Web sites once made front-page news, as the perpetrators intended. The impact of these acts has lessened as the volume has increased. The Web site that acts as the clearinghouse for many hacking reports, attrition.org, has stopped cataloging all Web site defacements because the frequency of such acts has outstripped the ability of the volunteers to keep the site up to date.

Compared to Web site defacement, vandalism within a network is more malicious in intent and less public. Today, security experts are noticing a rise in another form of online vandalism: hacktivist or cyberactivist operations. For example, in November 2009, a group calling itself “antifascist hackers” defaced the Web site of Holocaust denier and Nazi sympathizer David Irving. They also released his private e-mail correspondence, secret locations of events on his speaking tour, and detailed information about people attending those events, among them members of various white supremacist organizations. This information was posted on the Web site WikiLeaks, an organization that publishes sensitive and classified information provided by anonymous sources.

Leveraging online social media resources can sometimes cross over into unethical or even illegal territory. For example, activists engage in a behavior known as doxing to locate or steal confidential and personal records and then release them publicly to embarrass political opponents.

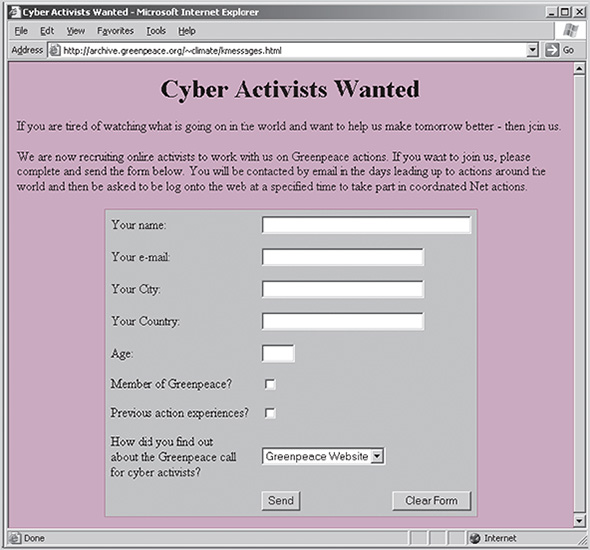

Figure 2-14 illustrates how Greenpeace, a well-known environmental activist organization, once used its Web presence to recruit cyberactivists.

Cyberterrorism and Cyberwarfare

A much more sinister form of activism—related to hacking—is cyberterrorism, practiced by cyberterrorists. The United States and other governments are developing security measures intended to protect critical computing and communications networks as well as physical and power utility infrastructures.

In the 1980s, Barry Collin, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Security and Intelligence in California, coined the term “cyberterrorism” to refer to the convergence of cyberspace and terrorism. Mark Pollitt, special agent for the FBI, offers a working definition: “Cyberterrorism is the premeditated, politically motivated attack against information, computer systems, computer programs, and data which result in violence against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.”

Cyberterrorism has thus far been largely limited to acts such as the defacement of NATO Web pages during the war in Kosovo. Some industry observers have taken the position that cyberterrorism is not a real threat, but instead is merely hype that distracts from more concrete and pressing information security issues that do need attention.

However, further instances of cyberterrorism have begun to surface. According to Dr. Mudawi Mukhtar Elmusharaf at the Computer Crime Research Center, “on October 21, 2002, a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack struck the 13 root servers that provide the primary road map for all Internet communications. Nine servers out of these 13 were jammed. The problem was taken care of in a short period of time.”* While this attack was significant, the results were not noticeable to most users of the Internet. A news report shortly after the event noted that “the attack, at its peak, only caused 6 percent of domain name service requests to go unanswered [… and the global] DNS system normally responds almost 100 percent of the time.”

Internet servers were again attacked on February 6, 2007, with four Domain Name System (DNS) servers targeted. However, the servers managed to contain the attack. It was reported that the U.S. Department of Defense was on standby to conduct a military counterattack if the cyberattack had succeeded. In 2011, China confirmed the existence of a nation-sponsored cyberterrorism organization known as the Cyber Blue Team, which is used to infiltrate the systems of foreign governments.

Government officials are concerned that certain foreign countries are “pursuing cyberweapons the same way they are pursuing nuclear weapons.” Some of these cyberterrorist attacks are aimed at disrupting government agencies, while others seem designed to create mass havoc with civilian and commercial industry targets. However, the U.S. government conducts its own cyberwarfare actions, having reportedly targeted overseas efforts to develop nuclear enrichment plants by hacking into and destroying critical equipment, using the infamous Stuxnet worm to do so.

Positive Online Activism

Not all online activism is negative. Social media outlets, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, are commonly used to perform fund-raising, raise awareness of social issues, gather support for legitimate causes, and promote involvement. Modern business organizations try to leverage social media and online activism to improve their public image and increase awareness of socially responsible actions.

0 comments:

Post a Comment